The square-jawed cowpoke has a blazing six-gun in one big fist and a leggy, low-cut blonde in the other. The wheels on the overturned buckboard behind them still spin in the blowing sand. This is the cover for Ace Publications' Western Trails, February 1948, 15 cents a copy.

The splashy sagebrush vision is one of more than a thousand colorful pulp magazine covers painted by Norman Blaine Saunders in the 1930s and '40s featuring dashing heroes and luscious heroines striking back at an assortment of thugs, bad weather and wild things. Lariat. Dynamic Adventures. Dime Detective. Buzzards of the Border. Tall, Dark and Deadly. The Martyred Virgins in the House of Torment.

"I never read any of the stories in those books in my life," said Saunders, 76, as he prowled through piles of dusty originals and engravers' proofs in his cluttered Manhattan brownstone.

Guarded on the landing by a rusty suit of armor, his third-floor studio is a dark Disneyland of violent imagination. It is littered with trench-coated spies, plainclothes cops in fedoras, stripe-shirted convicts, femmes fatales, cigarette girls, airline stewardesses, bludgeons, blades and battle-axes. There is a western saddle in front of the fireplace. On the mantel rests a skull wearing sunglasses.

"Generally speaking," he said, "the cover didn't have a damned thing to do with anything that was in the magazine. You see, a story can be very interesting and grip the readers and still have nothing in it that's picture.

"Very often the stories I drew for weren't even bought or scheduled yet. But always in the story there was somebody who pulled a zip gun to shoot somebody, right? So you'd try to think up something to go with it, maybe a circus train, for example. There wasn't a circus train in the whole damn magazine, but the editors didn't care; all they wanted was to catch somebody's attention. Then somebody would buy the book and get home and start to read it, and wonder where the hell was that thing on the cover, and they'd read some more and forget all about the damn circus train.

"The type of thing I came up with was what sold at the time: Guys with guns and gals with no pants on."

Saunders, who resembles the lean wranglers in his work, scattered worn sheaves of action scenes carelessly about, like leaves in a windstorm."These are Fiction House, Standard Publications, Street and Smith. Here's a Hopalong Cassidy; I did all the Cassidys. This is a Popular Publications.

"I have some more of these damned things, down in the kitchen, I think. Ordinarily I keep the pictures, but I don't have a complete list of the stuff.

"People and museums offer to buy 'em, but I won't sell. There's a simple reason for that: I can't keep the money. The government takes it from me. "

But he has, on occasion, broken his rule. "The Phillips Gallery (in New York) took two paintings not long ago that I got $200 for when I originally sold 'em to the pulps. After all these years, and I got more money for 'em than you could shake a stick at. It doesn't make any sense."

Nor does he see the sense in those who would make a cult figure of him.

"They have these pulp conventions," Saunders said. "I was out at one someplace--Akron, Ohio-- a couple of years ago. These people collect all the magazines, see, spend all their money that way, put 'em in the basement. Well, it was embarrassing. I'm not very good at that type of thing.

"I got all dressed up and people would look at me and I didn't know what the hell to do. So I'd walk around and look at the displays and all. What was there to look at? Crumbly old magazines. So I'd look at those, and they'd look at me, and I'd go downstairs and get a bottle and sit there and drink. And after an hour I'd come back and do it again. This went on for three or four days. It was crazy."

The stuff, after all, was tricks, Saunders said. He simply saved the New York newspapers--The Daily News and The Mirror-- and tried to find some oddball situation he could use: Gun battles on construction sites, on steamboats, in chemistry labs.

"When I finally understood what the business really was, I started just taking a standard scene that somebody had already used and moved it either backward or forward a minute or two minutes, and I'd have a different sequence of actions.

"For example: Two guys, one of them has a bottle in his hand and the other is pulling a gun, and the girl is screaming. You move it back a little: The guy has got this bottle--it might be acid or booze, depending on what label you put on it-- and he's going to throw it or drink it or pour it down the sink because the other one is a narcotics agent or something, right? And so he reaches in his pocket to get the gun. You move it forward a minute the other way: The guy has shot the other fellow, he's down, the acid is eating up the floor and the girl falls through the hole. Like that."

From the turn of this century until midway through it, the "pulps," which got their name from the rough-edged wood -pulp paper they were printed on, were major entertainment for tens of millions of Americans. The legacy of dime novels about larger-than-life characters (Buffalo Bill and Nick Carter), pulp magazines expanded during the 1920s to hundreds of gaudy adventure, romance, science fiction and western titles: The Thrill Book, Amazing Stories and Romantic Range. These lavishly illustrated publications were the nation's cheap thrills until television took over in the 1950s as a more accessible mass diversion. The formula-romance books of today are a throwback.

Saunders' pulp work began with Capt. Billy's Whiz-Bang and lasted straight through Ten-Story Western. At the end of the era, his career eased seamlessly into men's slick magazines, paperback and comic-book covers, and Wacky-Pack bubble-gum cards. He remains prolific as ever, filling notebooks with sketches and watercolors of his global wanderings.

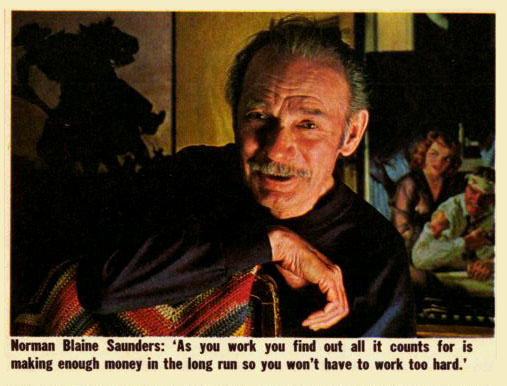

He paints abstracts "for the hell of it," but he won't sell them, either. "when you're young," he says, "you want to paint, you want to be someone, you want to make something of yourself. You want to be rich, hopefully immediately. And as you work time goes on and you find out all it counts for is making enough money in the long run so you won't have to work too hard."

And he's not at all happy with the current artist's lot.

"Magazine stuff is corporate now, it's the project of a whole bunch of people. It's no longer an artist putting out a picture. Everybody throws their two cents in and you lose everything; it stops being a single statement.

"You have to adapt the end result to the satisfaction of everybody involved, and there are bound to be a few idiots in there, and some of them with conflicting ideas of what is important and it all waters down to nothin'."

Saunders cannot pin down where his artistic talent came from ("I just picked it up"), but he does recall vividly the rural way stations that eventually led him to the big time.

"I was born in Minneapolis. My father was a railroad organizer, a Presbyterian minister and a game warden. All at once. He was pretty crazy."For a while when I was a kid we lived in a boxcar up on a siding, and my mother decided she'd had enough of that, so we had an 80-acre homestead for a while that my father bought some way or other. We lived there about five years, and he got tired of talking to himself and the trees and my mother and me, so he became a Christian. Just like that. When God finds you and Jesus calls you to the fold, as it were, you're dedicated and your wife can't tell you not to be. That was how he got out of the homestead and back in his element running off at the mouth and having fun.

"He let me do what I damned well pleased. It's embarrassing to be out saving souls and have your own kid be a nuisance, so if I wanted to sit around and draw, that was a good thing.

"I was about 12 when this traveling exhibit came to Roseau (Minn.) with a whole bunch of prints of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo and Rubens and other famous artists, and I would go over and spend the whole noon hour looking at these damn paintings. That was very inspirational. All the art I had ever seen before were calendars and the girls in their underwear in Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogs. Those were also very inspiring.

Then I saw the Saturday Evening Post, and here was the only other Norman besides me I had ever heard of, besides the livery stable man who was not very highly thought of in the community, and this Norman (Rockwell) was painting the covers. And I thought, my name is Norman, too, and I started right off to be an artist. I've been working at it ever since."

Saunders completed high school, worked in a general store and took a correspondence course in art from the Federal School in Minneapolis. The story of his first journey there reads like a pulp tale.

"I was hitchhiking, got into this Model T Ford with a big trunk strapped up and these two guys in front. One of them had a gun, a rifle. He said, 'Keep your eye peeled on the back, kid, see if there are any police or motorcycle cops or something.' What the hell was this? These two guys had robbed somebody, or tried to, out in North Dakota, and they had stolen this car from some farmer and were trying to get away. As we got to the outskirts Bemidji, I was getting awful nervous...

"There at the town they saw a sand pit with a big hole dug out of it, and they took this car over and got out and pushed it in. They went that way, and I went this way.

"That night I caught a freight train to Minneapolis. I took a streetcar ride to the end of the line, and there was a two-story bank there and a big sign: 'Robbinsdale, the home of Fawcett Publications.' I said, 'By gosh and by gracious, we got us a real true publisher here!' There was where they were printing Capt. Billy's Whiz Bang."

Saunders contributed cartoons to that popular compendium, and eventually submitted more ambitious works to Fawcett's Modern Mechanics.

He made a discovery early on: That paintings must come from life, even when the subject was fantasy. "If you do something from life, something that is really true that you see, the truthfulness and honesty in the picture comes through. I learned that. You got to paint a picture of a person, you get a person. You got to paint a picture of a dog, you get a dog. Even if you have to tack him up on the wall to see what he looks like."

In 1934 Saunders set off in a brand-new Pontiac with $1,000 in his pocket. He rented a flat on 67th street in Manhattan, and started making the rounds of publishing houses.

In those days, he said, "We generally dealt with art directors. They didn't let artists talk to editors. Editors are slightly feeble-minded, anyway; they don't know about pictures. I asked one of them, 'Gee whiz, how big can you make the bosoms on girls, anyhow!' He said, 'Oh set 'em as big as washtubs.' I said, 'Hell, what if I get 'em too big?' He said, 'That's impossible.' "

Saunders sold 75 to 100 covers a year at prices ranging from $75 to $150, "quite a chunk of change in those days." Detective Tales. North-West Romances. Two-Gun Western. The Lead-Slingers. Too Hot For Hell. The Hoodoo Herd of Mystery River.

During World War II, Saunders served first in the military police and later with the Army Corps of Engineers, laying a gas pipeline in China.

"I was a troubleshooter of sorts, I took care of problems," he said. "The main problem I took care of was how to stay out of work. You see, you go out and get a penny nail, a hammer and a piece of two-by-four, not too long, about three or four feet, something easy to carry. And you just walk around carrying that and look busy and don't do a damned thing. And if anybody asks you, you tell 'em, 'I'm on a detail.' "

He embroidered what he saw overseas, and painted guys who would "stand there and save the world for democracy" in man-oriented publications, including Adventure: The Man's Exciting Magazine of Fiction and Fact and Argosy.

Saunders married in 1946. Today he and his wife Ellene, an executive editor for Woman's Day magazine, have four grown children, all artists and all individuals one can recognize being chased and throttled and shot on the old Saunders covers that litter the studio.

"I don't want to sell 'em. Let my son worry about it when I'm dead and gone. Which should be about next week. "

Saunders made a sweeping gesture across the raw-boned sirens and the tough stubble-chinned sodbusters, and laughed his dry scapegrace laugh.

"Telegrams from limbo," he said, grinning.

**********************************