Another strange story came from a common source of strange stories: Women. Women are a topic of general conversation where ever soldiers are quartered. There they spend a great deal of time longing for their women back home--although not to the point that it interferes with any current amorous activity. This situation inveigled me into sketching every pretty native girl I saw. (An interesting sidelight on this affair is that beauty is where you find it, and if you real apply yourself you will find it in abundance.) I soon had more than enough material to make up an article on Central Asiatic women and their fashions, which was used by Today's Woman magazine.

While this project was under way, I became interested in women's hats, native styles, and local fashions. Sketches of this type could be extremely profitable to a dress or hat designer. I found a more immediate use for the information by giving it a twist: I sketched every man or boy I happened upon who wore an unusual hat. As it turned out, this required far more critical selection and elimination than I had anticipated. The majority of Chinese hats are home-made affairs, originality of design being as highly valued as protective qualities--or so it seemed to me. This article concerning the strange hats worn by the men of Central Asia was sold to True Magazine, along with one or two others covering the small matters of the Burma and Ledo Roads, and their construction, maintenance, and traffic.

Aside from the articles I sold during the year and a half I was in Asia, I compiled a folio of a thousand or more sketches which, though they do not seem to afford my unsuspecting friends and visitors the boundless pleasure I had anticipated, do nevertheless hold their interest. Many of them have proven to be of great value to me in my work, providing source material for my magazine covers and illustrations.

To turn a sketching trip into a financial success is dependent upon two vital qualities; strong arches are perhaps most important, while second is an alert mind. A weakness at either end can be counteracted by concentrated effort at the other.

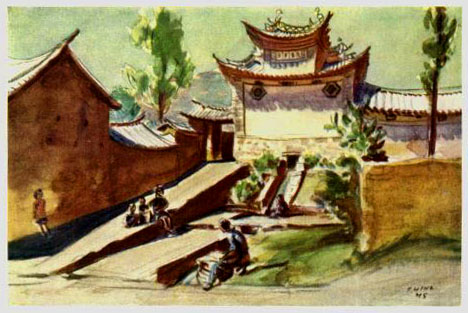

Granted that you have the foregoing as well as the ability to draw and paint with a degree of verisimilitude, you will need a supply of basic sketching equipment. First is a good pencil that leaves a sharp line when applied with a light hand, has good black quality and does not smear readily -- Prismacolor Black No. 935 is my personal choice. Paper is next in importance. All you will need is lots of it. As for colors, your personal inclination will dictate your choice of palette--I prefer Windsor Newton tube colors in a small metal water color box with mixing partitions. (However, the majority of my sketches were made with native colors purchased in China and India.) Three or four good brushes with the handles whittled down to fit your water color box and an assortment of colored pencils should just about take care of all your needs.

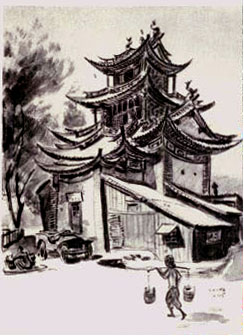

The procedure in starting a sketch will vary with the circumstances. If your subject matter is animate and in a striking pose or situation, catch its salient outlines first. This accomplished, you can tighten your drawing with confidence. At other times you may find an interesting locale or background with nothing of particular interest going on. Do not wait for something to happen. Start your sketch lightly, building it up carefully. Long before it is completed something will have occurred to dramatize the situation.

One of the reasons a sketch is so interesting is that it affords the artist an opportunity to bring into sharp focus or contrast the possibility inherent in the situation.

Always work the picture from its outside dimensions toward its center. In this way your proportions will be more accurate and valuable time will not be wasteed on minutia. Sketching from a standing position tends to keep drawing loose.