YOUR MODELS

The Chinese and Tibetans were not anxious to pose. Extremely self-conscious, they did not like to see themselves on paper. Their solution was to become overly-dignified and stiff, or to clown and appear ridiculous in the hope they would not be recognized. If they discovered that I was catching them in an informal pose, they would immediately "freeze" and show distress. American cigarettes or candy would usually take care of such difficulties.

PAINTING THE SUBJECT

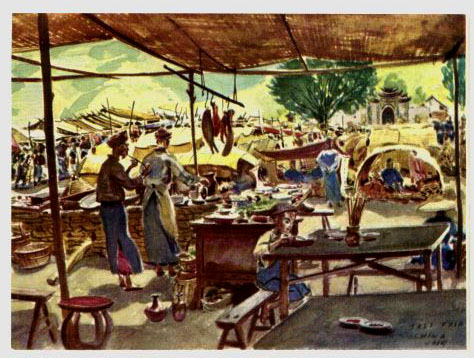

In the painting of the Tali Fair, the specific locale was chosen because of the marvelous food offered at this charming open air restaurant. I ordered a glass of water and a jug of local wine, opened up my sketching kit, and spread out my materials. After lightly penciling the stone wall and indicating the vertical uprights along with the matting that formed the roof, I blocked in the stools and tables, drank a glass of wine, and ate my salad greens and appetizers. While downing an excellent egg soup, I blocked in the line of vendors' stalls and sketched in the temple with its large tree. The mountain backdrop appeared on the scene simultaneously with a bowl of rice of similar proportions. At the appearance of some sweet-and-sour turnips, an assortment of smoked and pickled port sundries, and fish baked in one of the finest mustard sauces in the whole of China, I laid aside my sketch to devote my full attention to these matters of greater urgency.

With my teapot refilled at the end of the meal, I turned once more to the sketch, blocking in the figures lightly and floating a light green wash in the shadow areas of the mountain. While this was drying, I washed in all the shadow areas within the restaurant enclosure, starting with ochre at the stone wall and working toward the bottom, blending into a cool neutral color made with burnt umber and blue. While this dried, I turned the picture upside-down and washed a pale ochre and green over the entire mountain background. Following, I painted in a light yellow ochre for the booths and stalls in the center of the painting. This dry, I washed in the shadow areas, and indicated the people in blues and crimsons, along with the light detail in the temple. Next the green tree masses and the dark shadow areas in the various stalls, vendors' huts, and exhibits.

It was not till then that I started to pin down the details--the old man with the fur hat and pipe, the cook, the characters in the foreground, and the little boy with the chop sticks. (He's just wandered in to eat a bowl of rice prepared by his father the cook.) This I did with a wash of light burnt sienna, painting in the roof, the various supports, and the tables with their assortment of dishes, pots and pans, and buckets of water. As these areas dried, I noodled up the little details that caught my eye with spots of color.

FINISHING

I finally polished the whole thing off by painting in the dark accents with burnt umber--such details as the tree trunk, the tiles on the temple roof, and the darkest accents in the immediate foreground. I folded up my kit, paid the old man with the pipe, closed my sketch pad, and went off looking for high adventure.

LIGHT-TO-DARK PROCEDURE

Although my surroundings are not often as exotic as that, my work pattern there was typical. The light-to-dark procedure is often the easiest for me to execute, especially if the picture has a lot of small detail.

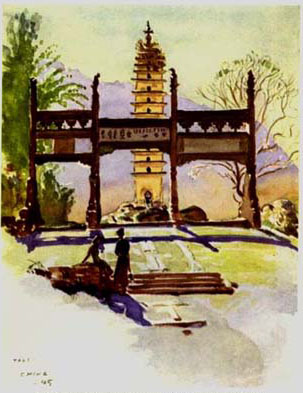

The temple gate picture with the ochre pagoda in the background was handled in this manner. First the sky, then the top half of the mountain was painted mauve; while still wet, the ochre was blended up from the base into it. Then the green foreground and the green in the trees were added, and finally the pagoda's light yellow ochre. The burnt sienna in the stone gateway, stairway, and figures; the dark mauve shadows and the dark burnt umbers made even darker with ultramarine when necessary brought the picture into sharp focus.